Weekday Names to Honor the Lord

by John P. Pratt

16 Sep 2018, 1 Jeshua (P), 7 Condor (SR)

©2018 by John P. Pratt. All rights Reserved.

Index,

Home

New weekday names are proposed for four sacred calendars based on existing Christian versions.

The names of the weekdays used by most countries are based on names of pagan gods which were associated with the seven anciently recognized planets. That has seemed acceptable to me until now because some of the sacred calendars are indeed planetary in nature. Recent developments have made it clear that it would be beneficial to switch to Christian names for certain sacred calendars. After this article discusses the need for new names, the history of the current names, and the already extant Christian names, the new names are then proposed.

1. Weekday Names

This article addresses the names of the days of the week. Hitherto in my articles, the usual weekday names in English have been used not only for our Gregorian Calendar but also for most of the sacred calendars based on the week. There is no need to change the entrenched weekday names used for the Gregorian Calendar, which also uses pagan names for many of the months. It is not considered to be a sacred calendar in my work. There are, however, two problems with such usage in sacred calendars.

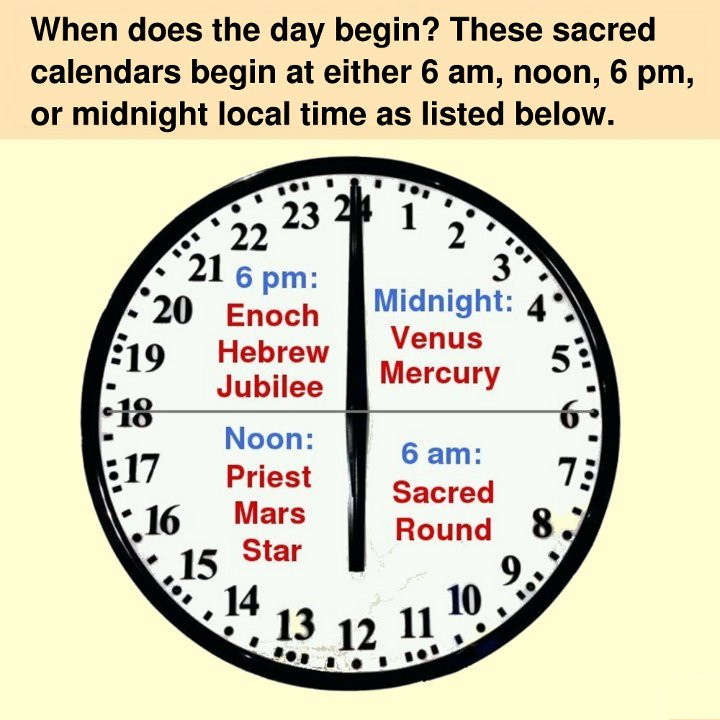

1.1 Begin Day

First, the time of the beginning of a day differs on sacred calendars from that of our usual calendar. The day on the Gregorian Calendar begins at midnight. None of the sacred calendars which are based on the week begin the day at midnight. Two of those calendars are the Enoch and Perpetual Hebrew. Those two, and well as their uniform versions, all use the same 7-day week and they all begin the day at 6 pm sundial time.

The time of the beginning of the day has been somewhat confusing in my papers where the timing of most sacred events is given with quarter-day accuracy.[1] An event often happens at a time of day which is holy on several calendars, which may all begin the day at different times. For example, some events happen on a Saturday evening which may be reported in my article as being on Easter Sunday on the Enoch Calendar. Surely some readers may wonder why an Easter Sunday event occurred on Saturday!

Thus, if the Enoch Calendar day names differed from the Gregorian names, then it would not be called Easter Sunday on that calendar, thus helping to avoid confusion.

1.2 Pagan Names

Second, in most languages, the names of the days of the week are named for pagan gods who were associated with the planets. As an astronomer, in my mind that was not a big problem because I think first of the planets. Anciently some true prophets were associated with certain planets, such as Enoch with Mercury and Abraham with Jupiter. To me it is plausible that the planet names came first, which were later associated with great men who later may have been worshipped as gods. That is, Enoch is often identified as the Greek Hermes and the Roman Mercury. Perhaps back in the beginning the planets may have been symbols of the seven angels of God, but then it got perverted.

Most people do not relate the weekday names to planets. If they care at all about the names, they think first of the gods and may not even know of the associated planet. Tuesday is named for the Norse god Tiw, Wednesday for Woden, Thursday for Thor, and Friday for Frigg. Do those names immediately bring certain planets to your mind?

|

Bracelet showing Roman gods/planets associated with weekdays.

(In Walters Art Museum. Click to enlarge.)

One point that tipped the scales for me that a name change is needed is that in modern revelation the Lord apparently avoids the use the pagan names of the days of the week. When He revealed to the Prophet Joseph Smith the day of the week on which to worship, He did not refer to it as "Sunday", even though that would have made the meaning perfectly clear. He referred to it as the "Lord's Day" (D&C 59:9-13), even as John the Revelator had done (Rev. 1:10). The only second witness of what day He referred to for Joseph was that He also called it "this day". If the reader refers to the date of the revelation, he finds it was indeed given on a Sunday. Thus, it appears that the Lord was purposely avoiding using the pagan name which associates that day with worshipping the sun.

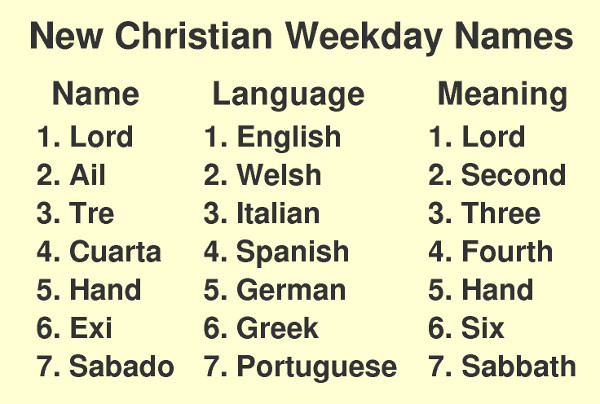

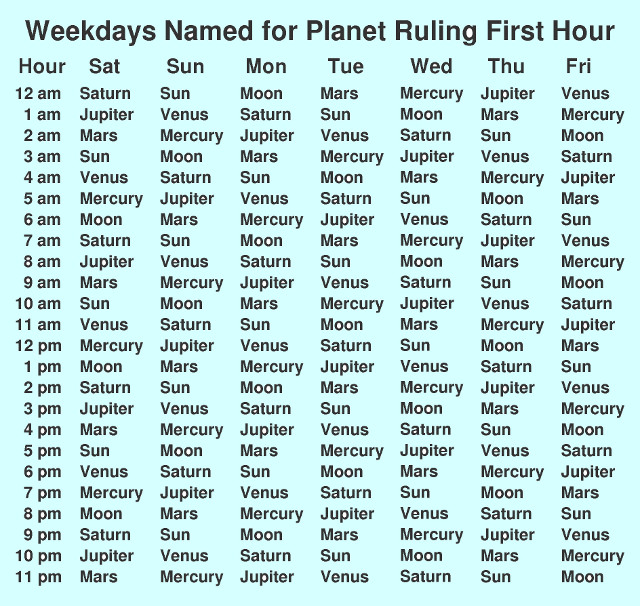

2. Historical Names

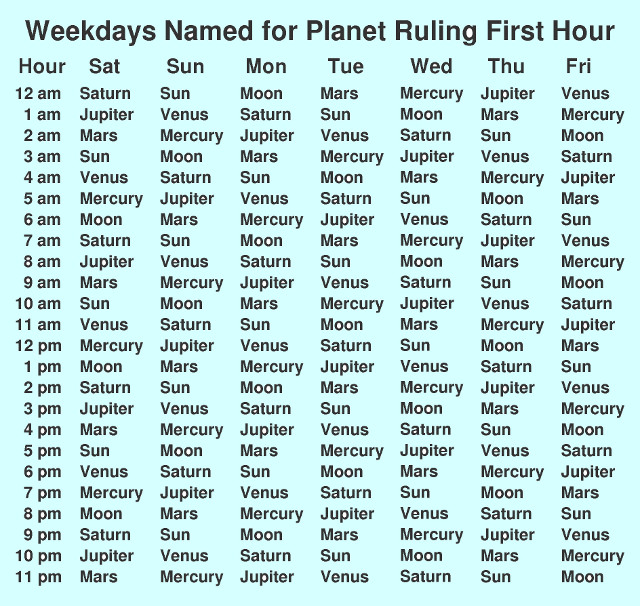

Weeks of seven days have been used since ancient Chaldean times and were associated with the seven visible planets: Moon, Mercury, Venus, Sun, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn (listed here in order of distance from the earth as understood by the ancients). The order of the names of the days of the week was chosen by having each planet take turns ruling in order over each of the 24 hours every day, continuously cycling through the day and even the entire week. The days were named for the planet which ruled over the first hour of that day.[2] That sounds like the work of very educated men who did not simply order them in a simpler manner. It is worth noting that the Priest Calendar groups weeks of 7 days into sets of 24, which suggests that more research is needed in this area. Let us now trace some weekday names throughout history.

2.1 Greek

|

Table 1. Early Greek weekday names.

Before their conversion to Christianity, the Greeks used the Chaldean planet name order for days of the week as shown in Table 1. That order has been preserved in many languages where the names of the weekdays are essentially the same as the planets. In English that is seen in the names of Sunday (Sun) and Monday (Moon).

When Greece became converted to Christianity they changed the names of the weekdays to those shown in Table 2. They are still used today.[3] Clearly the name of the first day was designed for Christians who worshipped on that day. The last two names were to reverence the Jews and the Old Testament acknowledging the seventh-day Sabbath and also Friday as the day of preparation for the Sabbath.

|

Table 2. Modern Greek weekday names.

Knowing this clarifies certain points of question. First, when John the Revelator referred (in Greek) to the "Lord's Day", there is no question that he referred to what we now call Sunday because the seven day week has not changed since then. Second, all of the gospels refer (in Greek) to the day of the Crucifixion as the "preparation" (Matt. 27:62; Mark 15:42; Luke 23:54; John 19:42) which is the Greek word for "Friday". Many modern translations of the Bible simply translate the word as "Friday", which makes the meaning clear. Modern proponents of a Wednesday or Thursday crucifixion suggest that perhaps that word referred to preparation for Passover which could occur on other days. That only confuses the scriptural witness which declares that it was a Friday. The Crucifixion day being a Friday is also indicated because the women could not anoint the body with spices on Friday evening because that began the Sabbath, so they came early Sunday morning instead (Luke 23:54-24:1).

2.2 Roman

The Julian Calendar was named for Julius Caesar who implemented it for the Roman Empire on 1 Jan 45 BC (Julian). It was a huge step forward to fix the length of the year to be 365.25 days with a year of 365 days and an extra day in February every four years. At that time there was no official use of the 7-day week at all in the Roman Empire. It was kept, however, for religious purposes by the Jews and Christians.

The Romans had an 8-day cycle of market days which was not always of fixed length. It was to designate business days rather than to accurately keep time. Thus, references in the New Testament about days of the week refer to the traditional Hebrew cycle.

The Romans associated gods with the planets, following the Greek tradition, but before Constantine it is not clear from my research that those gods and planets were associated with certain days there. All of this changed when Constantine the Great was converted to Christianity.

2.3 Constantine

|

Constantine the Great.

Constantine became Emperor of the Roman Empire in AD 306. During a battle in AD 312 Constantine prayed to the Christian God of whom he had been taught by his father. The Church historian Eusebius, bishop of Caesarea, knew Constantine personally and wrote a biography of him. He reported that as Constantine prayed at midday for God's help, he and his whole army saw a cross in heaven, brighter than the sun, bearing the inscription "By this sign you shall conquer." Constantine testified that when that night he prayed for an interpretation, Christ appeared to him in a dream and commanded him to make a likeness of that sign to use as a safeguard in battle against his enemies.[4]

In AD 313 Constantine established religious toleration and criminalized the persecution of Christians in the Edict of Milan. He had succeeded Diocletian under whose reign had been the most severe persecution of Christians, so that was a total reversal of policy for the empire.

Then Constantine wanted to unite his pagan empire together with Christians. He knew that some pagans worshipped the sun on the first day of the Greek week and that some Christians in Rome reverenced that same first day of the week to celebrate the resurrection of Christ,[5] so on 7 Mar 321 (J) he issued an edict which integrated the 7-day week into the Julian Calendar and mandated the entire empire to keep the weekly day of the sun holy by closing businesses on that day,[6] hopefully uniting both pagans and Christians.

One researcher states that Constantine named the weekdays, making a change to the Christian and Jewish tradition of simply numbering the days from "first" to "seventh" (Luke 24:1). Probably following the Greek usage (see Table 2), he reportedly changed the name of the first day from "feria prima" (first holiday) to "Dies Dominica" (the Lord's Day). Moreover, the name of the seventh day of the week was changed to "Sabbatum" (Sabbath) to honor the Jews. The proposed names had been previously applied by the Church in Rome only to the days of the holy week before Easter, but Constantine mandated that these liturgical names be given to every day of every week![7]

These new names apparently did not come into general use in the empire. Today they are known only as the Latin liturgical day names because the Church kept them. Those names are Dies Dominica, feria secunda, feria tertia, feria quarta, feria quinta, feria sexta, and Sabbatum. Many researchers are unaware that Constantine proposed these names[8] and I have not been able to verify it through multiple sources. The planetary gods had been associated with a 7-day cycle in Greece and apparently that usage for the week became popular throughout the empire. One country, however, later began officially using the Latin liturgical day names as discussed in the next section.

2.4 Martin of Braga

|

Archbishop Martin of Braga.

In science many laws or principles are associated with two names, one of the man who discovered or invented the idea and the second of the man who convinced others to use it, which seems equally important or it would have to be discovered again.[9] Moreover, the typical case is that the one who sold the idea is remembered only to later discover that he did not originate the idea nor claim to have done so, but was only making people aware of it. Such is the case with Martinho de Dume, known also as Martin of Braga, who was responsible for getting the existing liturgical weekday names used in Portuguese.[10]

In the sixth century AD, Archbishop Martin of Braga (a district in Portugal) taught while converting the Portuguese to Christianity that weekday names should not be used which refer to pagan gods.[11] He advocated the Latin liturgical names. The Portuguese and their Brazilian descendants took this to heart and renamed their weekdays domingo ("Lord's Day"), segunda-feira, terça-feira, quarta-feira, quinta-feira, sexta-feira, and sábado. These names, translated into Portuguese by St. Martin, are still used today in Portugal and Brazil.[12]

One thing I noticed while living in Brazil was that by having both the names sábado and domingo for day names there was no confusion between them. Those were just the names of the days. In English, people use the word "Sabbath" for the holy day of rest, which is Sunday for most Christians. In my church I heard children being taught that God made the earth in six days and then rested on Sunday, the seventh! Moreover, some calendars now show Saturday and Sunday as the last two days of the week (the "weekend"), which was even done in the bracelet illustrated above. I grew to really like having the two distinct names for the first and last days, which avoided confusion. Moreover, using numbers for the other day names made it clear that sábado was the seventh.

That these names refer to both Saturday and Sunday as holy also works well with sacred calendars because the holy weekday on the Priest Calendar begins at noon on Saturday and ends at noon on Sunday. Thus, half of Saturday and half of Sunday are holy on that calendar. For this reason it may be best where possible to hold Christian Sunday worship meetings in the morning.

Given this history and even current usage, let us now turn to proposing new names for the weekdays on the Enoch and Perpetual Hebrew calendars, which are based on our usual 7-day week but begin the day at 6 pm.

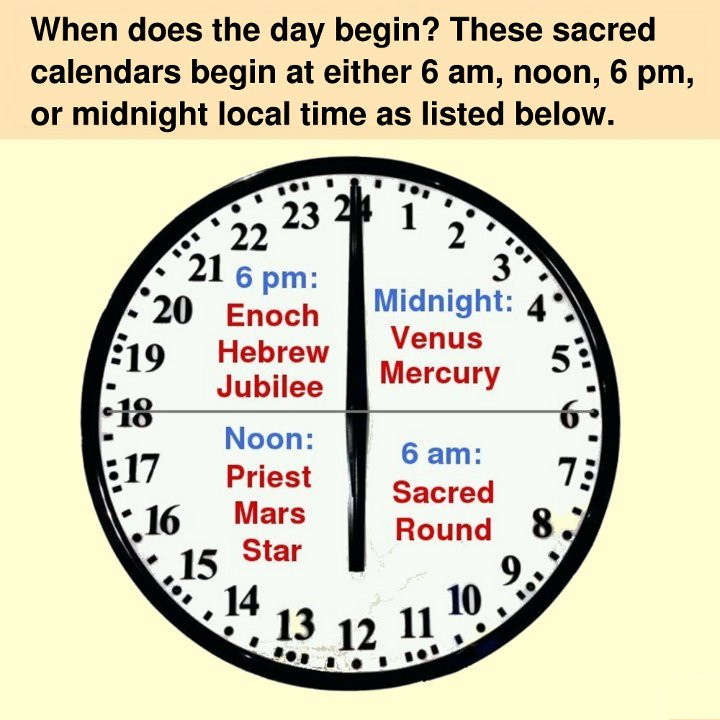

3. New Proposed Names

|

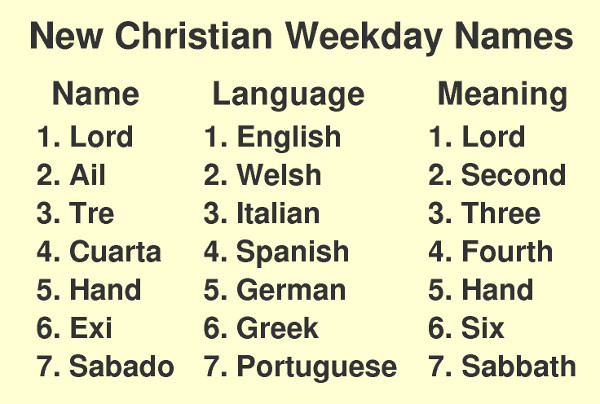

Table 3. Proposed new weekday names.

Now that we have reviewed the need for new names for weekdays, it is time to propose them. We could follow the lead of St. Martin and use those from the Catholic liturgy, purportedly dating back to Constantine. The names Domingo and Sabado are easy to remember but most of us do not connect numbers to days of the week. It would be good, however, to learn the numbers of the weekdays because numbers are used on the Priest Calendar. Thus, using day names which refer to numbers could be a quick and easy method to identify week days, as is done in Greek and Portuguese.

The following criteria were used to choose new names:

- The concept of "Lord" should be kept for the first day.

- The names 2-6 should be associated with the day numbers.

- The first 3 letters should be a pronounceable abbreviation.

- Each name should begin with a different letter (for single letter abbreviations).

- Each name should come from a different language and be a simple, short word.

- The first letters of the names should spell a word or other mnemonic.

- The concept of "Sabbath" should be kept for the seventh day.

That turned out to be difficult but possible to fulfill. With those criteria in mind, here are the new proposed names (see Table 3).

- Lord (means "Lord" in English).

- Ail (means "second" in Welsh).

- Tre (means "three" in Italian).

- Cuarta (means "fourth" in Spanish).

- Hand (means "hand" — with 5 fingers — in German).

- Exi (pronounced "Hexi" means "six" in Greek).

- Sabado (means "sabbath" in Portuguese, emphasis on first syllable, pronouned SAHB-bah-doe).

These names refer to 24-hour days which begin at 6 pm and will be used in my work when needing to refer to days on the Enoch and Perpetual Hebrew calendars. The acrostic spelled by their first letters ("latches") refers to fastening or linking things together, such as the latch on the left end of the bracelet shown above, which latches the two ends to each other. Hence, these letters could help link Christians together who speak various languages.

4. Conclusion

It was suggested that it would be convenient to have new names for the weekdays on the Enoch and Perpetual Hebrew calendars and their uniform versions because (1) their days begin at 6 pm so it would differentiate them from Gregorian days and (2) there are indications that the Lord prefers not use names of pagan gods for day names. Historical attempts to change the weekday names from the usual planetary connections were reviewed, with the most successful being the Greek and Portuguese names. As Christians, they honor the Lord on the first day and called the seventh day "Sabbath". It is noted that reverencing both first and last days as sacred works well for sacred calendars which often have holy events occur on both of those days.

Seven new names were proposed which follow the Portuguese lead as to meanings. In addition, the names are each from a different language and begin with different letters which together spell the word "latches", suggesting that they can help latch all Christians together. Their overall purpose is to glorify God.

Notes

- The notation used to identify the quarter day in my articles is the use of an asterisk (*) ("aster" meaning "star") to indicate when the stars are seen at night. These sacred calendars use the average time not the actual observational time, so, for example, the time of sunrise is considered to be 6:00 am throughout the year. Thus, am* is from midnight to 6 am, am is from 6 am to noon, pm is from noon to 6 pm and pm* is from 6 pm to midnight.

-

Note that the seven planets are listed in reverse order (as anciently understood) starting with the furthest and then cycling through them repeatedly all week, at which time it starts over. The days are named for the planet that rules the first hour, which is why the table begins on Saturday.

- See Falk, M., "Astronomical Names for the Days of the Week", Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada, Vol. 93, p.126, whence the names came for Tables 1 and 2. The modern Greek names can be verified by simply checking an English-Greek dictionary.

- Eusebius, Life of Constantine, 27-29, quoted by the Christian History Institute #107 Constantine's Vision. The text of Eusebius as quoted there is as follows: 27. Constantine Chooses Christianity ... So he considered which god he could rely on for protection and help. It occurred to him that, of the many emperors who had preceded him, those who had put their hope in a multitude of gods and served them with sacrifices and offerings had been deceived by flattering predictions and oracles promising prosperity and come to a bad end, without one of their gods warning them of the impending wrath of heaven. On the other hand, the one who alone had condemned their error, honoring the one Supreme God throughout his whole life [i.e. his father], had found him to be the Savior and Protector of his empire. Reflecting on this ... he decided it would be great folly to join in the idle worship of those who were no gods, and to err from the truth after such convincing evidence. For this reason he felt bound to honor his father's God alone. 28. Constantine's Vision Accordingly Constantine called on him with earnest prayer to reveal to him who he was, and stretch forth his right hand to help him in his present difficulties. And while he was thus praying with fervent entreaty, a most extraordinary sign appeared to him from heaven — something which it might have been hard to believe had the story been told by any other person. But since the victorious emperor himself long afterwards declared it to the writer of this history, when he was honored with his acquaintance and society, and confirmed his statement by an oath, who could hesitate to believe it, especially since other testimonies have established its truth? He said that about noon, when the day was already beginning to decline, he saw with his own eyes the sign of a cross of light in the heavens, above the sun, and bearing the inscription, "By this symbol you will conquer." He was struck with amazement by the sight, and his whole army witnessed the miracle. 29. Constantine's Dream He said that he was unsure what this apparition could mean, but that while he continued to ponder, night suddenly came on. In his sleep, the Christ of God appeared to him with the same sign which he had seen in the heavens, and commanded him to make a likeness of that sign which he had seen in the heavens, and to use it as a safeguard in all engagements with his enemies.

- "Did Constantine Change the Sabbath from Saturday to Sunday? summarizes: "As a shrewd political genius, his scheme was to unite Christianity and paganism in an effort to strengthen his disintegrating empire. Constantine knew that pagans throughout the empire worshiped the sun on 'the first day of the week,' and he discovered that many Christians and especially in Rome and Alexandria also kept Sunday because Christ rose from the dead on that day. So Constantine developed a plan to unite both groups on the common platform of Sunday keeping. On March 7, 321 A.D., he passed his famous national Sunday law".

- Veith, Professor Walter J., PhD, "Constantine and the Sabbath Change" (24 Apr 2010). "Summary: Sunday was transformed from a pagan to Christian day of worship in part due to Constantine's contributions in the fourth century AD." Veith quotes the edict: "On the venerable Day of the sun let the magistrates and people residing in cities rest, and let all workshops be closed. In the country, however, persons engaged in agriculture may freely and lawfully continue their pursuits: because it often happens that another Day is not so suitable for grain sowing or for vine planting: lest by neglecting the proper moment for such operations the bounty of heaven should be lost." He gives the reference for that quote as Philip Schaff, History of the Christian Church Volume 3 (Edinburgh: 1884) p. 380, footnote. When Constantine referred to the "day of the sun" he referred to the well known Greek tradition of using the Chaldean names where the sun is tied to the first day of the week. Many histories take this to mean that Constantine officially introduced the pagan week into the Julian Calendar, which is not true: he was focused on Christianity. Note that the edict mentions both sowing grain and planting vines, both of which are seasons on the Jubilee Calendar used by the Essenes at that time, and so he may been appealing to them too. Veith goes on to state, "Close on the heels of the Edict of Constantine followed the Catholic Church Council of Laodicea (circa 364 AD): 'Christians shall not Judaize and be idle on Saturday (Sabbath), but shall work on that Day: but the Lord's Day they shall especially honour; and as being Christians, shall, if possible, do no work on that day. If, however, they are found Judaizing, they shall be shut out from Christ.'" For that quote Veith gives the reference Rev. Charles Joseph Hefele, Henry N. Oxenham (trans.), A History of the Church Councils from 326 to 429 Volume 2 (Edinburgh: T. & T. Clark, 1896) p. 316.

- The full names include the word "feria" as in "feria secunda". The list of names provided in this article, as well as why the Portuguese version of the word ("feira") is still used today in Portugal and Brazil, is discussed in "Why do we use the suffix 'feira' for the Days of the Week in Portuguese?" posted by Pedro Santana, State University of Londrina (UEL), Paraná, Brazil (30 May 2013). It states: "In those times, Easter would last one week, and all of the days were called feriae (holiday). There was feria secunda (second holiday), feria tertia and so on. When Constantino coverted to christianism, he changed the name of feria prima to Dominica (Lord's Day), where 'Domingo' came from. And for the seventh day, he reintroducted 'Sabbatum', in respect to the Old Testament. But Constantino went further, demanding these names to be used for every day of the year!" It should be noted that Easter Week was the week before Easter which is similar to the Hebrew Calendar in which, if Passover falls on a Sunday, then Easter occurs on the following Sunday after the holy week of Passover. In my research, no second witness was found attributing these names to Constantine. The deciding factor for me to include this source as reliable was that only an emperor could include the word "feria" (holiday) in the weekday names. That is what caused the author to ferret out the origin of that word because its homonym is still retained in his Portuguese language and many people ask the question of its origin. I cannot visualize anyone in the Catholic Church applying names used only for Easter week to every day of the year. An emperor could indeed have done that!

- Achelis, Elisabeth, "Constantine And The Week", Journal of Calendar Reform (June 1954): "He [Constantine] had always been impressed with the Christian ideas about the calendar. He liked their observance of a seven-day week, with the first day set aside as a day of rest and worship. The week was a complete novelty to the Roman calendar, which had its months subdivided into the impractical Nones, Ides and Kalends.

Nine years after Constantine became Emperor he issued an edict introducing the seven-day week into the Julian calendar. The weekdays had no names but were known only by numbers. The week displaced the old Kalends, Nones and Ides, and eventually the days acquired the names of the seven heavenly bodies--Sun, Moon, Mars, Mercury, Jupiter, Venus and Saturn."

- Examples from my field of astronomy are the Titius-Bode Law which for centuries until my youth was known as Bode's Law. Then someone learned that the law had been discovered by Titius and only made popular by Bode. It is the same with the Hertzsprung-Russell diagram.

- See for example Ribeiro, Patricia, "The Religious Origin of the Days of the Week in Portuguese" (25 Mar 2018) which states "Martinho de Dume based the names on the full observance of Easter week" which seems to imply that he originated the Portuguese weekday names rather than just translated them.

- "Martin of Braga", Wikipedia, summarizes: "Martin objects to the astrological custom of naming the days of the week after gods (planets). Due to his influence, Portuguese and Galician (which, at the time, were one single language) are the only Romance languages where the names of the days come from numbers and Catholic liturgy, rather than from pagan deities." Martin's original quote is also provided from his De correctione rusticorum: "for the infidels have angered God and do not believe wholeheartedly in the faith of Christ, but are such disbelievers that they place the very names of the demons on each day of the week, and speak of the day of Mars and of Mercury and of Jupiter and of Venus and of Saturn, who never created a day, but were evil and wicked men among the race of the Greeks." The reference for that quotation is given as Braga, M. & Dumium, P. & Seville, L. & Barlow, C. W.(2010). Iberian Fathers, Volume 1 (The Fathers of the Church, Volume 62). Washington: The Catholic University of America Press.

- Note that the Portuguese version of the names uses "feira", which means "market", instead of "feria" which means "holiday" in both Latin and Portuguese. When I lived in Brazil, I was taught that "feira" is used because formerly the marketplace moved around to various locations on different weekdays. I have no idea whether or not that was true at the time of Martin and if that was his reason for changing the word. It seems like a good choice because to anyone it would sound strange to call every day a holiday!