Reprinted from Meridian Magazine (26 Apr 2006).

©2006 by John P. Pratt. All rights Reserved.

| 1. Education in Science |

| 1.1 Knowledge vs. Ignorance |

| 1.2 Levels of Ignorance |

| 2. Education in Religion |

| 2.1 False Teachings |

| 2.2 Edges of Knowledge |

| 2.3 True Doctrine |

| 3. Conclusion |

| Notes |

We are all eager to pass our knowledge on to the next generation, so they can avoid making our mistakes and can begin building where we left off. Surely that is a true principle because we can see the great technological advances in civilization by having done that. But is there also a need to teach what we have not learned?

There is a well-known saying that "It's not what I don't know that gets me in trouble, it's what I know that ain't so." Are there things you learned in science classes that you later discovered are just not true? Are there things you learn in church that you later discovered are just not true? When that happens, one's belief in science or faith in religion can be shaken to the core. Is there a way to prevent this confusion?

Now ask yourself whether you believe that to be true. When I asked that question to my wife, she rehearsed that same story. Then I asked, "Do you believe that?" After thinking for a moment, and apparently mentally reviewing families she has known, she replied with some certainty, "No, that just isn't true. I know families where both parents have blue eyes and not all of the children have blue eyes." Isn't that interesting. Apparently she had never really taken the time to compare what she learned in school to real life in that case. One brown-eyed child did. He was disappointed in school not to learn why he had brown eyes and both of his parents had blue, so he went on to do more experiments in the field to discover why.[1] According to recent articles on the internet, eye color is a subject which is not understood in all its details.[2] If that is the case, why didn't they teach me that in school?

To me this is a very serious question. In classes designed to educate, clearly we want to teach what we think we have learned. We want our children or students to learn quickly the results of past experience in history and the sciences, as well as skills such as reading, writing, math and arts. Surely we don't want to have the teacher tell us that they don't know anything and that we all need to start from scratch. But just where is the correct balance between teaching what is known and what is unknown?

|

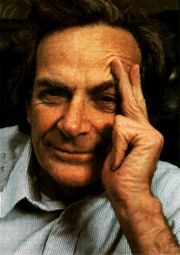

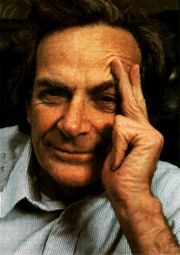

Perhaps what might be the best approach in all teaching would be to spend about 90% of the class time teaching what is believed to be true, but then at least 10% of the time inspiring students to continue on and learn specific things which are just not understood. Perhaps we should all follow Feynman's example.

Let's go back to the eye-color example. The results of Gregor Mendel's experiments with peas were published in 1866, but largely unrecognized until after 1900.[3] He found that crossing purple-flowered peas with white-flowered peas produced mostly plants with purple flowers, some with white, but none in between. That result can be explained with the dominant-recessive gene theory. But if that is all that is taught in school, the students think that the subject is all done, that there is nothing more to be learned and there is no incentive to do more experiments. How many years was it after that before someone discovered that if you cross a red snap dragon with a white one, the result is often pink? It is now more than a century after Mendel, and we still don't have a clue about hazel eyes or grey eyes. My whole point is that if the class had ended with the simple statement like, "While this theory explains certain very simple cases and is often true, there are still many problems which we do not understand, such as pink snap-dragons and hazel eyes." If classes had explained our weaknesses as well as our strengths, then we might have explained hazel eyes long ago. Many of us have had a false sense of security about what we know.

But the way, in defense of the teaching of genetics, apparently the problem has been corrected to a large degree. If you enter "genetic eye color" into a web search engine you will find several articles which explain the subject well and make it clear that we don't know all the answers. One article is an ideal role-model for just what is proposed in this article.[4] My point is that I wish such teaching was common a century ago.

It is also important to explain where even our most certain knowledge stops and ignorance begins. For example, Sir Isaac Newton's law of gravity when tested with experiments in the laboratory has a 100% success rate as far as I know. That is wonderful, and why we call it a "law" rather than a "theory." But every law is effective only in a certain domain where it obtains. Whenever a principle in science is taught, it would be wonderful to also explain the limitations on the experiments. In the case of gravity, we could explain that we don't know if this law applies to subatomic particles and subatomic distances, or across intergalactic distances. Moreover, I was appreciative of the first teacher who taught me that we have no idea why Newton's law works. That is, Newton did not explain exactly why the earth and moon would somehow "know" how hard to pull on each other, but only that we could calculate the acceleration of each toward the other by using his equation. Often the great steps in knowledge have been taken by those who were either taught that we didn't know it all, or who realized that what they had been taught was inadequate. Such considerations led Albert Einstein to propose a whole new theory of gravity.

When listening to sermons being preached in church, it can be instructive to question whether or not the doctrine being taught is really true. Can you remember where it says in scripture the point being taught? Has a living prophet taught that concept? If so who, when, and where?

And again, might it be a good idea occasionally to explain just what we do not know? Sometimes this is easy, as in examples when the Lord has told us that some things are not public information, such as the exact time of his Second Coming (Matt. 24:36), or of the details of the fate of the sons of perdition (D&C 76:44-47). Sometimes it is harder, as when we have misunderstood a scripture because of a poor translation or because we have confused a figurative meaning for a literal or vice versa. One solution to the question of correct translation is to consult several translations. There are some excellent tools for doing this, such as a book putting 8 independent translations of the New Testament side by side.[5]

Let me give an example of the first category. Have you ever heard it taught in church that Alma gave a wonderful discourse in which he taught that faith is like a seed, which will grow if it is planted in the heart and then nourished? Now read that sentence again and ask yourself if that is true. Is that what Alma taught? If not, then exactly what did Alma teach? Is it important to get it right?

To me it is important enough to mention here that it is not at all what he taught. He taught that the word of God is like a seed to be planted in the heart, not that faith is like a seed. Faith is exercised in planting the seed and nourishing it (Alma 32:28-42), but it is the gospel that we must plant in our heart. Now is that just a picky detail, not worth clarifying? To me it makes a huge difference, because Alma is apparently telling us both to study the scriptures and also to listen to the word directly from the light of Christ in our hearts. That calls for action on our part, and it is the faith which leads us to perform that action. It is the same symbolism that he Savior used in the parable of the sower (Mat. 13:3-23).

Speaking of parables, consider one more example. How often have you heard it taught that Christ taught in parables so that his hearers could better understand his meaning by using examples familiar to them? Now, is that true? Is that why he taught in parables? Actually we know that exactly the opposite is true. He explained to his disciples that he used parables to hide the deeper meaning from hearers so that they would not understand (Mat. 13:10-15). Then he explained the meaning to his apostles who also would not have understood otherwise (Mat. 3:18-23).

One thing that has frustrated me in many church classes is the teacher who loves a wonderful discussion and asks the class their opinion of the meaning of some doctrine. About ten different responses are listed on a chalkboard. Now that may all be fine and often generates interest, but then I expect the teacher to conclude the discussion by telling us the correct answer by quoting what the prophets have indeed said on the subject. But there are many teachers who drop the discussion there, perhaps not wanting to offend someone who gave an incorrect response. But we have come to church to learn the true word of God, to have it planted in our hearts, not to see the confusion demonstrated by the variety of responses from the class. Often the church's official position is clearly stated in the manual, but the teacher never mentions it.

My point here is that when we do indeed know the truth, we should teach it with power and conviction, and back it up with references to official sources.