Dead Sea Scrolls May Solve Mystery

by John C. Lefgren and John P. Pratt

Reprinted from Meridian Magazine (12 Mar 2003)

©2003 by John P. Pratt. All rights Reserved.

Index,

Home

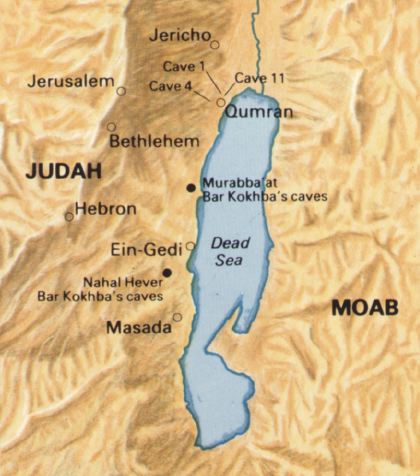

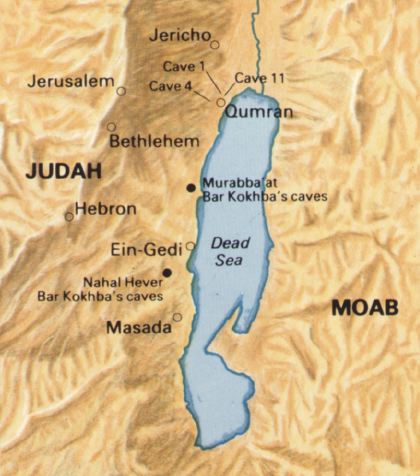

Using the moon to determine Qumran calendar dates in the Dead Sea Scrolls sheds

light on the longstanding enigma of when the priestly temple courses served.

The Dead Sea Scrolls have provided a wealth of information about religious practices during the

first century or so BC in the community at Qumran near the Dead Sea. A surprisingly large

portion of the scrolls deals with keeping time, which was essential for knowing exactly when the

sacred feasts prescribed in the law of Moses should be celebrated.[1] The scrolls make it clear that

the group at Qumran felt that the other Jewish sects were mistaken in the calendar they were using,

which was based on the phases of the moon. This was probably one of several reasons that caused

them to withdraw from Jerusalem and to celebrate their own feasts at the times they felt were

proper according to what has become known as the Qumran calendar.

|

Many Dead Sea Scrolls were found near Qumran.

Some of the scrolls provide long lists of dates and ample detail about the calendar, but apparently

no one has correlated the Qumran calendar to our Gregorian calendar. That is, when the scrolls

speak of a certain date on which a festival was held, just exactly what date did that correspond to

on our calendar? The best correlation to our calendar so far is that the two principal calendar

scrolls date to about 50-25 BC, based on the style of handwriting.[2] Fortunately, that is much

more precise than the dates ascribed to the entire set of scrolls and the community in general, being

from the late second century BC through the destruction of the temple in AD 70.

The purpose of this article is to attempt to correlate the beginning date on the two principal Qumran

calendar scrolls to our calendar. Having done that, and found independent corroboration, we can

then answer a long standing historical question about when each course of priests officiated in the

temple at Jerusalem. Resolving that problem has implications for to all of Judaism, not just the

sect at Qumran. Next month's article will focus on what it means to Christian chronology.

1. The Qumran Calendar

While several documents discovered at Qumran give schedules of events according to their calendar, the best descriptions of the workings of the calendar itself are probably found in the

Book of Jubilees and the Book of Enoch.[3] Although those books are not included in our Bible

today, both were held in high regard at Qumran, equal to others we now include in the Old

Testament.

The calendar had 364 days each year, beginning on a Wednesday every spring. It had four quarters

of exactly 13 weeks each, so that every quarter-year began on a Wednesday. Each quarter had

three months, the first two having 30 days, and the third having 31 days. The months were

numbered from 1 to 12, beginning in the spring. Thus, it had a feature desired by many modern

businessmen: it was so tightly tied to the week that every day occurred on the same

day of the week every year. In particular, their sacred feast days always occurred on the fixed

days listed in Table 1.[4]

| Holy Day | Qumran Calendar | Hebrew Calendar |

|---|

| New Year's Day | Wed, 1st day, 1st month | 1 Nisan (1st month) |

| Passover | Wed, 15th day, 1st month | 15 Nisan |

| Waving of Sheaf of Barley | Sun, 26th day, 1st month | 16 Nisan |

| First Fruits of Wheat (Pentecost) | Sun, 15th day, 3rd month | 6 Sivan (3rd month) |

| Day of Remembrance (Trumpets) | Wed 1st day, 7th month | 1 Tishri (7th month) |

| Day of Atonement | Fri, 10th day, 7th month | 10 Tishri |

| Tabernacles | Wed 15th-22nd, 7th month | 15-22 Tishri |

Table 1. Holy Days on the Qumran Calendar occurred on the same day every year.

|

Cave 4 is the nearest to Qumran.

Of course, having only 364 days, the calendar year was 1.24 days short of a true solar year of

365.24 days. They must have had some method for inserting an extra week often enough to keep

this calendar aligned with the seasons, because some of the offerings, such as First Fruits, had to

occur at certain seasons of the year, when the barley or wheat would be ripe. While scholars have

acknowledged that an intercalation system was needed (meaning inserting extra days to align with

the solar year), they have noted that no method is mentioned in the scrolls.[5] In this article, we

both attempt to precisely date one seven-year period, as well as propose a possible intercalation

method.

1.1 The Priest Cycle

Before proceeding to date the Qumran Calendar, we need to understand what we shall call the

Priest Cycle. Officiating duties at the Temple of Solomon were divided among 24 families who

descended from Aaron, the brother of Moses (1 Chron. 24:1-18). These family divisions are

usually translated "courses" in the Bible (1 Chron. 23:26, Luke 1:5). A priest from each family

presided at the temple for one week, beginning about midday every Saturday.[6] Their names and

the order in which they presided are given in Table 2. Thus, it took 24 weeks to complete the entire

cycle. If this calendrical cycle could be correlated to a known date, and if it were known to be

continuous, then the cycle could potentially be used to establish other historical dates. For

example, when the angel Gabriel appeared to the priest Zacharias in the temple, he was on duty

representing the course of Abijah (Luke 1:5-20). That course only officiated every 24 weeks, so it

would be a big clue to when that event occurred if it were known when that course officiated.

| The Priest Cycle |

|---|

- Jehoiarib

- Jedaiah

- Harim

- Seorim

- Malchijah

- Mijamin

- Hakkoz

- Abijah

|

- Jeshua

- Shecaniah

- Eliashib

- Jakim

- Huppah

- Jeshebeab

- Bilgah

- Immer

|

- Hezir

- Aphses

- Pethahiah

- Jehezekel

- Jachin

- Gamul

- Delaiah

- Maaziah

|

Table 2. The names of the Heads of each Aaronic Priesthood family, in the order in which they served in the temple (1 Chron. 24:1-18).

|

Qumran and Dead Sea as seen from a cave.

So what has this priest cycle got to do with the Dead Sea Scrolls? It turns out that the scrolls may

be the key to understanding the Priest Cycle because all of the calendrical tables of events include

not only the day of the month and week, but also the name of the course officiating during that

week. That does not mean that the society at Qumran was in charge of making the roster for temple

priesthood service. Rather, it was simply the accepted convention to name every week. It was an

excellent way to have a double check on exactly what date is meant, and provides a way to detect

copyist errors. For example, today we often include the week day along with the date on

invitations, such as to wedding receptions. That serves as a reminder as to exactly what date is

intended. The method used at Qumran to refer to a Wednesday was, for example, to call it 4

Gamul. The means the fourth day (Wednesday) of the week called Gamul (which was when that

priestly course served in the temple). Days of the week at that time were simply numbered from

Sunday, being the first day of the week. Saturday was simply referred to as the sabbath, usually

meaning the day the new priests began duty, rather than the last day of their duty. It is really

fortunate that this method of giving both a day and month as well as week day and week were used

to record events in the scrolls because errors in the scrolls can be immediately detected. And a

compliment is due for the scribe because there are only a handful of mistakes in hundreds of dates

listed.

1.2 Seven-Year Cycle

The scrolls also give us one big clue about how the Qumran calendar might have been intercalated.

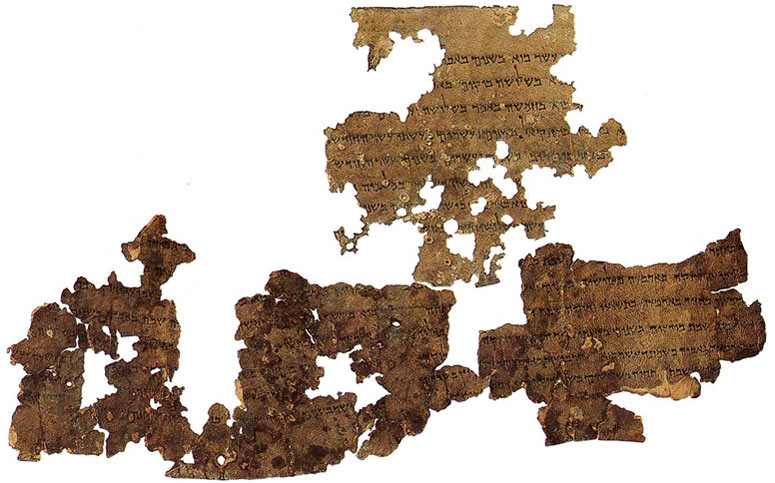

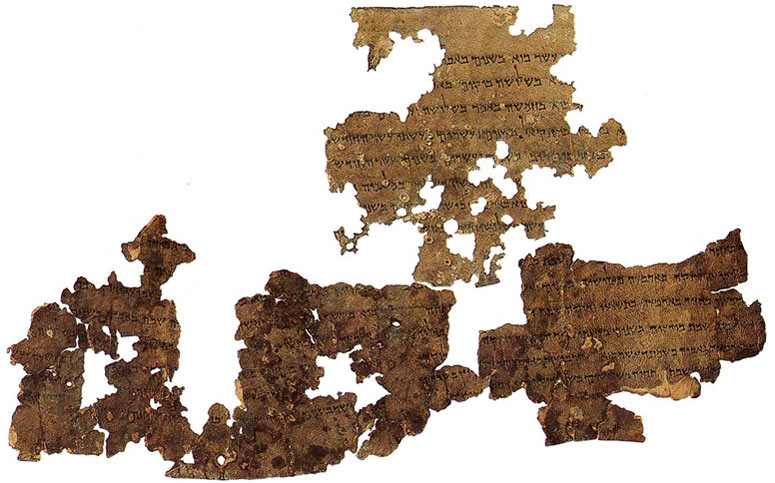

The two most famous and detailed calendar scrolls are called 4Q Calendar Document A and B (also

called 4Q320 and 4Q321) because they were found in the 4th cave discovered at Qumran. The latter

("Scroll B") is a continuous 7-year listing of events: one year of dates of lunar observations

followed by a 6-year list the dates of both lunar events and also the feast days and how the

beginnings of each month aligned with the week and priest cycle. It is clear that every year in that

period had exactly 364 days. This table also establishes that the Priest Cycle was understood to be

a continuously repeating cycle, which is confirmed by other Hebrew writings.[7].

|

Entrance to Cave 4, where Calendar scrolls were found.

The fact that it is a 7-year listing with the last 6 years treated as a separate entity is an important

clue. It means they had almost certainly noticed that six years completes a cycle where the same

priest would again be officiating on New Year's Day. That is, 6 years of 52 weeks each exactly

equals 13 Priest Cycles of 24 weeks (6 x 52 = 13 x 24 = 312 weeks), so the two cycles would

begin to repeat.

1.3 Sun Rises in East

Another important point is that the first day of that 6-year period is given more attention than any

other day in the scrolls. Scroll A begins with this description of that day:

"...to display itself from the East, and shine in the centre of the sky, at the base of

the vault, from evening to morning, on the 4th (Wednesday) of the week of the

sons of Gamul, in the first month of the first year."[8]

To clarify, here is our interpretation of that important description:

" (the sun) ... rises due east, and shines at the celestial equator, on the horizon at

dawn (as night becomes morning) on Wednesday, 4 Gamul, in the first month of

the first year."

Other references in the scrolls make it clear that this day was also the first day of the first month in

that first year.[9] The celestial equator is the great circle in the sky used by astronomers from

ancient times to divide the northern half of the sky from the southern half. To an astronomer, that

is an obvious meaning for the phrase "center of the sky" in the above quotation. Every year on

March 20 or 21 on our Gregorian calendar, we have the "first day of spring" (vernal equinox),

when the sun in its annual trek, crosses the celestial equator from the southern half of the sky to the

northern. On that morning, it rises most nearly to due east. One crucial piece of data to understand

the importance of this event for those at Qumran is that the Book of Enoch explicitly states that the

year is to begin when the sun rises in the east such that the day and the night are of equal length,

and then begins moving north (Enoch 71:12-13). That is an excellent description of the day of the vernal

equinox. In fact, "equinox" means "equal days and nights."

This method for beginning the year is very different from the method used in Jerusalem at the time.

On the Judean calendar, the spring New Year's Day occurs at a new moon, chosen such that the

next full moon occurred on or after the spring equinox.[10] Because the equinox occurs on March

20/21 on our calendar, that means that the Judean calendar could begin as early as March 7

(because the new moon is two weeks before the full moon), whereas the Qumran calendar year

would have begun on a Wednesday about March 21.

Astronomers at Qumran would have been aware that the way their calendar worked is that every

year the true equinox would come earlier by about 1 1/4 days. That means that when they inserted

an extra week, they would pick the first Wednesday after the true equinox, rather than before. To

see this, let us remember that the way our Gregorian calendar works is to insert a leap day on

February 29th nearly every 4 years to keep the spring equinox on March 20/21. The Qumran

calendar apparently has an uninterrupted span of 7 years, each of 364 days, so that after seven

years, it loses 7 x 1.24 days = 8.68 days from the true year. So, ideally, the 7 years should begin

about 4 days after the equinox (March 25th), so that each year thereafter would begin about 1.24

days earlier. That way, after three or four years, the year would begin very near the true equinox

and still be on a Wednesday. After seven years, the beginning would be on March 16-17th, and it

would be time to insert an entire extra week so that the cycle could begin again about March 23

24th. But that extra week would not quite make up the deficit of 8.68 days. Adding 7 days every 7 years makes the average year become 365 days rather than 364. If one more week were added every 28

years then the average year length would be 365.25 days, which is an excellent value.

The main point here is that the ideal time for the Qumran calendar to begin a seven year cycle is the

first Wednesday after the spring equinox. The sun rises at different places along the eastern

horizon every day, and makes an annual circuit from the southeast through northeast and back

during the seasons. The time when the place of sunrise on the horizon changes the most is at the

spring and autumn equinoxes, the two days of the year when the sun rises most nearly due east. At

that time the shift in the position of the sun as it rises on the horizon is more than two solar

diameters every day, so it is easy to determine the precise day when the sun rises most nearly due

east.

1.4 Qumran Sundial

|

Qumran Sundial could determine the equinox.

If our understanding of how the calendar was intercalated is correct, then those at Qumran would

need a way to determine the day on which the sun rose due east. Many ancient cultures did that by

erecting a pillar or marker to align with a mountain peak or other horizon feature. Stonehenge in

England is a classic example, but it aligned with the summer solstice rather than the spring

equinox. Is there any physical evidence at Qumran that they were interested in determining the day

of the vernal equinox?

Here the answer is a resounding "Yes." A limestone sundial has been discovered at Qumran. It

was designed to measure the sun during the year rather than during the day. After studying it, two

researchers concluded:

"It could have been used to handle the discrepancy between 365.25 days and a

calendar year of 364 days. It allows the determination of the cardinal points and

fixing a calendar whose seasons are as near as possible to the signs of sun, moon

and stars." [11]

Thus, there is strong supporting evidence that the Qumran calendar was indeed intercalated with a

method involving actually measuring when the sun arose in the east, as directed by the Book of

Enoch.

1.5 "First Year"

Note also that in the above quotation from the scrolls that the beginning day of the six-year period

is called the first day of "the first year." First year of what? To answer this, we must remember

that the Lord instructed Moses to count years by sevens (Lev. 25:4). Most likely, it the

"first year" meant the first year of a 7-year cycle, and that the year listed before it was the last

(sabbatical) year of the previous cycle. This suggests that the intercalation of an extra week of

days which would be needed to keep synchronized with the seasons probably came at the end of

the sixth year of the 7-year cycle. That is consistent with the fact that the Judean lunisolar calendar

was also often intercalated in the 6th year to minimize the length of the year when crops were not available.[12]

Thus, the current state of understanding is that the Qumran calendar has a year of 364 days

comprising 12 months of 30 or 31 days each and has holy days occurring every year on known fixed

days. Moreover, the Priest Cycle was uninterrupted for at least one 7-year period. What has not been

known is just when that 7-year period occurred, except that it is estimated to have begun about 50-25

BC. Let us now attempt to discover the precise date of that 7-year listing.

2. The Correlation

If all the information that the scrolls contained were a list of the dates of the beginnings of the

months, the feast days, and the courses of the priests, then the scrolls might have begun on

any Wednesday at all in the historically plausible time period. That is because we have not known

exactly when the priests served, or even if they served as one continuous cycle. Thus, if one starts

on any Wednesday near the spring equinox, which is assumed to be the week of Gamul, then all of

the first days of the months and the feasts will fall in exactly the priestly weeks listed (except for

scribal errors). It would tell us that indeed we have the dates of the feasts correct, and that they

occurred on the same days of the Qumran year annually, but that is all. It would be of no use

whatever to indicate the starting year.

2.1 Lunar Phases

Fortunately, the same two calendrical scrolls mentioned above provide another set of clues. They

give many dates of the last day of the lunar month and also of the full moon. We are not aware of

anyone who has attempted to correlate this listing of the moon's phases to the known lunar phases

during the possible time period, so we will now describe out approach to do that.

Scroll A includes a listing of the last day of every lunar month. Even though the words "last day

of lunar month" are not found there, the meaning is clear because there are alternate listings as the

"29th" and "30th" every month, correlated to the date and week day. The true lunar month contains

29.53 days (the period between new moons), and so an excellent approximation is simply to

alternate months of 29 and 30 days, for an average value of 29.5 days. Scholars apparently agree

that the last days of the lunar month are indicated. In all cases known in the ancient world, the

lunar month begins at the new moon, and that is our hypothesis.[13]

|

Fragment of Calendar Document B (4Q321).

Perhaps one reason that the scrolls have not been precisely dated in the fifty years since their

discovery is that there is uncertainty as to what is meant by the last day of the lunar month. There

is a one to two day period when the moon is invisible during every cycle of phases. The last day

of the lunar month might refer to the last day the thin crescent is visible before dawn, or it could be

day of the new moon, or even the day after when the new crescent may still not be visible after

sunset. This latter was the interpretation of those in Jerusalem at that time. Thus, there is a three day

uncertainty which makes it hard to know just what phase is implied, and hence difficult to pinpoint

any date.

We propose that the key to solve the problem is to focus on the full moons, which are also listed.

Observing the full moon is a better reference point because it is independent of the details about

how the month begins. In other word, while "new moon" is of uncertain meaning, "full moon"

has always meant "when the moon is fully illuminated." Fortunately, scroll B lists dates for the

full moon for the same three-year period, along with also repeating the listing of dates of the end

of the lunar month for those years. It then continues through the six-year period with the dates of

the holy days and first days of each month. Because the lunar cycle lasts 29.53 days, and begins

at the new moon, we need only correlate the full moon days listed with the phase of 14.76 days

because the full moon occurs halfway through the cycle, on the average.

Focusing on the full moons immediately makes it clear how the end of the lunar month was defined. The last days of the month are nearly always listed as occurring 13 days after the full moon, whether or not the month has 29 or 30 days. That means the last day is on day 27.76 on the average (14.76 + 13 = 27.76). That is nearly two full days before the new moon (on 29.53), so it indicates that the last day of their month was the last day that the old crescent was visible before dawn. That is very different from how things were done in Jerusalem where new crescent was observed, but is consistent with one proposed method for how a Galilean calendar might have been regulated.[14] Thus, at Qumran, the first day of the month was apparently the first day that the moon was not visible.

|

|

| Wed 27 Mar 140 | 28.2 | 0.4 |

| Wed 23 Mar 137 | 27.6 | -0.2 |

| Wed 20 Mar 134 | 27.0 | -0.8 |

| Wed 20 Mar 123 | 28.8 | 1.0 |

| Wed 28 Mar 113 | 28.0 | 0.2 |

| Wed 25 Mar 110 | 27.4 | -0.4 |

| Wed 21 Mar 107 | 26.7 | -1.1 |

| Wed 26 Mar 99 | 29.2 | 1.4 |

| Wed 22 Mar 96 | 28.6 | 0.8 |

| Wed 27 Mar 83 | 27.2 | -0.6 |

| Wed 23 Mar 80 | 26.5 | -1.3 |

| Wed 27 Mar 72 | 29.0 | 1.2 |

| Wed 23 Mar 69 | 28.4 | 0.6 |

| Wed 20 Mar 66 | 27.7 | -0.1 |

| Wed 28 Mar 56 | 26.9 | -0.9 |

| Wed 24 Mar 53 | 26.3 | -1.5 |

|

| Wed 28 Mar 45 | 28.8 | 1.0 |

| Wed 25 Mar 42 | 28.1 | 0.3 |

| Wed 21 Mar 39 | 27.5 | -0.3 |

| Wed 21 Mar 28 | 29.3 | 1.5 |

|

|

Table 3. Possible first days for the Qumran Calendar. The upper dates are unlikely because the scroll was written between 50-25 BC.

|

According to the listing for the first month of the first year, that day happened to also be the last day of the lunar month.[15] Thus, it would have had a mean lunar age of about 27.8 days.

Another consideration is that the scribe might have been copying a table from the past, rather than making a current calendar. That seems unlikely because we do not have tables covering many years, and it seems that it was only possible to project up to six years ahead until another measurement of the equinox would ascertain whether one or two weeks would need to be intercalated. Accordingly, let us make a table of every date from 150 BC through 25 BC on which the

moon's age (days from new moon) was within 1.5 days of matching that on the Qumran calendar tables, on a Wednesday from March 20-28 (Gregorian calendar, being about a week after the spring equinox). We also list the "error," meaning the difference between that age and 27.8, the ideal age on the last day of the lunar month.[16]

From Table 3, we see that the most likely date for the beginning of the first year of the Qumran

sabbatical cycle is either Wed 25 Mar 42 BC or Wed 21 Mar 39 BC. They both occur during the period when the scroll was written and each has an error of only 0.3 days from the recorded lunar phase. One thing that favors the first date is the symmetry between the two dates. With both of them having the same discrepancy from the true full moon, we would expect that if the first date were the correct starting date, then the second date would be listed in the 6-year listing has having exactly the same lunar phase. Checking the listing we find that is true: the first day of the fourth year is also the last day of the lunar month, just as was the first day of the first year:

"(The next lunar month ends) on the fourth of Shecaniah, on the first (day) of the first (solar) month."[17]

No too much weight should be given to this coincidence because it would only be off by one day at most in any case. Nevertheless, it does favor the earlier date because the synchronism is perfect.

2.2 Sabbath Year Cycle

Another point in favor of the 42 BC choice is that it agrees with one of the proposed years for the

7-year sabbatical cycle of the other Jewish sects of the time. While those at Qumran differed with

others about the kind of year to use, they might well have agreed with them about the 7-year count.

We do not wish to make too much of this coincidence because the sabbatical cycle has been a

subject of debate,[18] and even if it were known, it might not have agreed with the Qumran group.

It does appear to be, however, supporting evidence that the counts may have agreed.

Now let us consider a second witness that the date Wed 25 Mar 42 BC is indeed the correct

choice to be the first day of the first month of the first year of the Qumran tables.

3. Corroboration

Fortunately, there exists strong supporting evidence, totally independent from the Dead Sea

Scrolls, that we have indeed found the correct date. In AD 70, Titus led the Roman Army against

Jerusalem, and the temple was burned. The Jewish historian Josephus

gives a detailed eye-witness account. He gives the date of the burning of the temple as 10 Ab.

This date was significant to him because it was a date stated in the Bible that the temple was

burned by Nebuchadnezzar over six centuries before (Jer. 52:12-13). Josephus stated, "it was the

tenth day of the month Lous [Ab], upon which it was formerly burnt by the king of Babylon."[19]

Other Jewish sources provide more chronological details. Finegan summarizes

"the tradition that the First and Second Temples were destroyed on a day after the

Sabbath, during a post-Sabbatical year, and

during the weekly service of the course of Jehoiarib, on the calendar date of the

ninth day of Ab equivalent in the year AD 70 to Aug 5."[20]

Here we get several more clues. The day after the Sabbath would be Sunday and AD 70 matches a

post-Sabbatical year according to the traditional understanding of the cycle. But for us, the

important part is that it occurred in the week of Jehoiarib. Finegan's date of Sun 5 Aug AD 70 is

on the Julian calendar used by historians, and is the same as the day Sun 3 Aug AD 70 on our

modern Gregorian calendar, which is used throughout this article.

So now the question is, if we use the correlation we have proposed that Wed 25 Mar 42 BC was

in the course of Gamul, does that sync up with Sun 3 Aug AD 70 being in the course of

Jehoiarib?

The answer is in the affirmative, so here we find a second witness of the correctness of our anchor

date being Wed 25 Mar 42 BC. In fact, not one of the other possible starting dates listed in Table 3 would cause Sun 3 Aug AD 70 to fall in the course of Jehoiarib. That has at least two implications. First, it strongly implies that we have found the correct date. Secondly, it is consistent with the traditional understanding that the temple priest cycle was unbroken from at least 41 BC through

AD 70.

4. Conclusion

The conclusions of this article are first, that all of the usually understood features of the Qumran

calendar are correct in that it had a 364-day year beginning on a Wednesday, with holy days

occurring on fixed days every year. We propose that the calendar was intercalated to keep the

feasts at the proper season by inserting an entire extra week after the sixth year of each 7-year

count. Moreover, we propose that another entire extra week must have been added about once

every 28 years, such that the year would begin on the Wednesday on or after the spring equinox.

The Qumran sundial was most likely used for the purpose of knowing when to insert this extra

week. By correlating the tables of the full moon in the historically probable period from 50-25

BC, we deduce that the first day of the first year mentioned in both Calendrical Documents A and

B most likely refers to Wed, 25 Mar 42 BC. Of all plausible dates after 150 BC that is the only choice that would cause the date of the destruction of the temple, Sun, 3 Aug AD 70, to be in the course of Jehoiarib, as recorded.

Notes

- Michael Wise, Martin Abegg, Edward Cook, The Dead Sea Scrolls, A New Translation (New York: Harper-Collins), p. 13, estimates about 40% of the non-Biblical text deals with the calendar.

- Shemaryahu Talmon, Jonathan Ben-Dov, and Uwe Glessmer, Discoveries in the Judaean

Desert - XXI, Qumran Cave 4 XVI Calendrical Texts, (Clarendon: Oxford University Press,

2001), p. 68: "The scroll was penned in a 'late Hasmonean or early Herodian book hand' ...

Accordingly, 4Q321 can be tentatively dated to c.50-25 BCE. Of all the

calendrical Scrolls, this is the best example of a well-executed script by a

highly qualified scribe."

- Both are found in The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha, ed. James Charlesworth (New York:

Doubleday, 1985). The Book of Enoch (1 Enoch) is on line at www.johnpratt.com/items/docs/enoch.html

- This list matches holy days listed in the scrolls discussed in this article. The so-called "Temple

Scroll" also lists other holy days for the First Fruits of Wine, First Fruits of Oil, and the Wood

Offering, which are not mentioned in the law of Moses. See Yigael Yadin, The Temple Scroll (New York: Random House, 1985). For a discussion of how a 364-day calendar based on the calendar of Enoch could serve as a modern calendar with an intercalation scheme nearly identical to that proposed in this article, see Pratt, John P., "Mapping Time," American Mathematical Monthly 106 (Jan 2000), pp. 92-99 at www.johnpratt.com/items/docs/mapping_time.html#6.

- Yadin, op. cit., p. 86, offers, "There is no mention in the scrolls published so far of how the

sect made up for the loss of 1 1/4 days in their calendar, but they may have had a system of adding

one month every twenty-four years." His suggestion, however, seems extremely unlikely as it

would break the synchronism with the week.

- Jack Finegan, Handbook of Biblical Chronology (Massachusetts: Hendrickson, 1998), p. 133,

quotes Mishna sources that "the Sabbath-day changeover from one course to the next the outgoing

priests offered the morning sacrifice and the incoming priests offered the evening sacrifice."

- Roger Beckwith has suggested the Priest Cycle began anew every year in autumn in the Judean

month Tishri. (Finegan, p. 134, quoting Beckwith, RQ 9, 1977: 81, 85-90). But that speculation

was apparently based only on the coincidence that Jehoiarib began serving in Tishri in the first year

listed in the scrolls, and that when the Jews returned from the exile to Babylon they began the

temple courses in Tishri. Simply looking at the later years in the 6-year series shows that the

cycle was continuous.

- Martinez, Florentino G., The Dead Sea Scrolls Translated (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1996), p.

452. It is ironic that one of the only mistakes in the companion scroll (4Q321) lists this very important

day as occurring in the week of Delaiah, the week after Gamul (Frag 2, Col 1, Line 8, subline 1), but that cannot be

because it does not fit with any of the dates which follow on that same scroll. Apparently that error

is not generally known because Finegan quotes it without comment (p. 137). Correcting that error

is crucial for our argument because it refers to the first day of their first year.

- 4Q321, Frag. 4, col.iv, line 8: "The first day of the first month falls in the week of Gamul" and

4Q321a, Frag. 1, col I, Line 2: "On the fourth day in the week of Gamul, which

falls on the first day of the first month."

- "Sanctification of the New Moon," The Code of Maimonides, trans. Solomon Gandz

(New Haven: Yale University Press, 1956), p. 16: "if the court has ascertained by calculation that

the tekufah (equinox) of Nisan would fall on the 16th day of Nisan or later, it intercalated the

year."

- Uwe Glessmer and Matthias Albani, "An Astronomical Measuring Instrument from Qumran",

The Provo International Conference on the Dead Sea Scrolls, Technological Innovations, New

Texts, and Reformatted Issues, edited by Donald W. Parry and Euguene Ulrich (Boston: Brill,

1999), p. 442.

- Maimonides, p. 21: "Nor was it proper to intercalate a Sabbatical year; for then everyone had

to depend upon the aftergrowth ... It was customary, however, to intercalate (if need be) the year

preceding a Sabbatical year.... If, however, the year required intercalation on account of the

tekufah (equinox) ... the court was obliged to intercalate the year at all events."

- Some researchers have speculated that the month might have begun at the full moon, which is totally without precedent and hard to take seriously. Surprisingly, translators

have given that possibility enough credence to translate "duqah" as "lunar observation"

rather than simply "full moon." Others actually translate the word as "new moon" (Martinez, 4Q321, Frag. 1, col 1, line 1, p. 454). Talmon et al. state on p. 34,

"Two theses have been put forward in recent years. One school maintains that the new moon

signals the beginning of the month in Convenanters' tradition, in accordance with a common trait

in Semitic culture. However, in wake of Milik's interpretation of the puzzling pericope 4Q320 1 i

1-5, another school argues that the lunar month was understood to begin at full moon. This

faction failed to notice that according to the above calculations the luminaries were created on lunar

day 0, i.e. one day before the actual beginning of the first month. Accordingly, on the day of its

creation the moon would have been only thirteen parts of fourteen full. Thus, the month cannot be

said to begin at full moon. Alternatively, if on the day of its creation the moon was indeed full, in

accordance with Milik's interpretation of 4Q320, then it must be assumed that, for whatever

reason, the lunar month was calculated to begin on the day after the full moon, an unprecedented

practice in Semitic cultures." We take the position that the scrolls make

perfect sense with the traditional interpretation that the lunar month begins at the new moon and

that "duqah" means "full moon."

- Lefgren, John C., April Sixth (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1980), p. 44: "The first day of Nisan for the Galileans and the Pharisees seems to have been at sunrise after a moonless night..."

- It is an interesting coincidence that the new moon was so close to the first day of the solar year. It may have contributed to their making the prolonged comments about that first day, because there are hints in the Book of Enoch that ideally the new year should also begin with a new moon. See the discussion of Enoch 73:13-16 by John P. Pratt in "Celestial Witnesses of the Meridian of Time," Meridian Magazine (10 Jul 2002) at www.johnpratt.com/items/docs/lds/meridian/2002/meridian.html#2.

- The moon's age was calculated by subtracting 9.7 from the Julian Day number and taking the remainder when divided by 29.5305956. For example, 25 Mar 42 BC is Julian Day 1,706,168. Dividing 1,706,158.3 by 29.5305956 yields 57,775.95288. So the age is .95288 of a month, or 28.14 days. This calculation can be performed for any date on line at www.johnpratt.com/items/calendar/calcalc/calcalc.html and choosing the "Planets" calendar and then the "Moon" version, and also the Gregorian calendar.

- 4Q321, Frag. 1, Col. 3, Line 7, Subline 2, Talmon translation.

- Finegan, pp. 116-125 gives a good summary of the sabbath cycle debate. The traditional

view, established by Zuckerman in 1856, is that the first year of the 7-year cycle, counting from

the fall, was, for example, from the fall of 44 BC to the fall of 43 BC. In 1973, Wacholder

revised the cycle to be one year later. If that revision is correct, it would agree that the spring of 42

BC was a "first year" which agrees with the results of this paper for the Qumran community.

But in 1979 Blosser produced evidence to accept to original traditional view. So the issue does not

appear to be not settled.

- Flavius Josephus, Wars of the Jews VI.iv.5 (6.250), in The Complete Works of Flavius Josephus, trans. William Whiston (Grand Rapids: Kregel, 1981) p. 580.

- Finegan, p. 275.